No. 301, Fuel System Integrity. This standard specifies requirements for the integrity and security of the entire fuel system.

It is important to note that National School Bus Yellow (NSBY) is not an FMVSS, although many people believe it is. School bus yellow was adopted by the first National Conference on School Transportation (as it was then called) in 1939 and was already an industry-wide standard in use by the states for decades. The lack of an FMVSS does not mean the federal government has not expressed an opinion on school bus color. In NHTSA’s Highway Safety Program Guideline 17, it recommends school buses be painted NSBY and goes so far as to suggest that any school bus that is converted for purposes other than transporting children to and from school and school-related activities be painted a different color.

Because our industry moves 24 million students twice each school day during peak traffic times in every community regardless of its population, school bus crashes are an inevitable risk. Most every crash is reported by the media in some form or manner. However, when we look past the visual of the wrecked school bus, do we realize that nearly all of the students are either uninjured or suffer only minor injuries? This is the “value added” of the April 1, 1977, standards.

Pete Baxter is the school traffic division director for the Indiana Department of Education and the general conference chair for the 2010 National Congress on School Transportation. He is also a former president of the National Association of State Directors of Pupil Transportation Services and the National Association for Pupil Transportation.

[PAGEBREAK]

What I’ve Seen in My 50 Years

By George Horne

I may be the only contributor to this section who has experienced most of the innovations, having had my first experiences with school buses more than 50 years ago. You will learn from some outstanding experts the details of developments that have contributed to the unprecedented records of safety and service about which we proudly boast. With less detail to specifics, let me share some developments that I have experienced during my association with school buses and with student transportation, in general.

Pete Baxter has addressed construction “standards.” What I recall as major developments in school bus design and construction — besides federal motor vehicle safety standards — likely will seem strange to younger readers. The trucking industry may have provided the catalyst for some improvements, especially as they relate to school bus chassis. Development of war materiels and space vehicles has resulted in many improvements in metal, fabrics, fastening devices and parts manufacturing. We should give credit where credit is due!

A long, short list

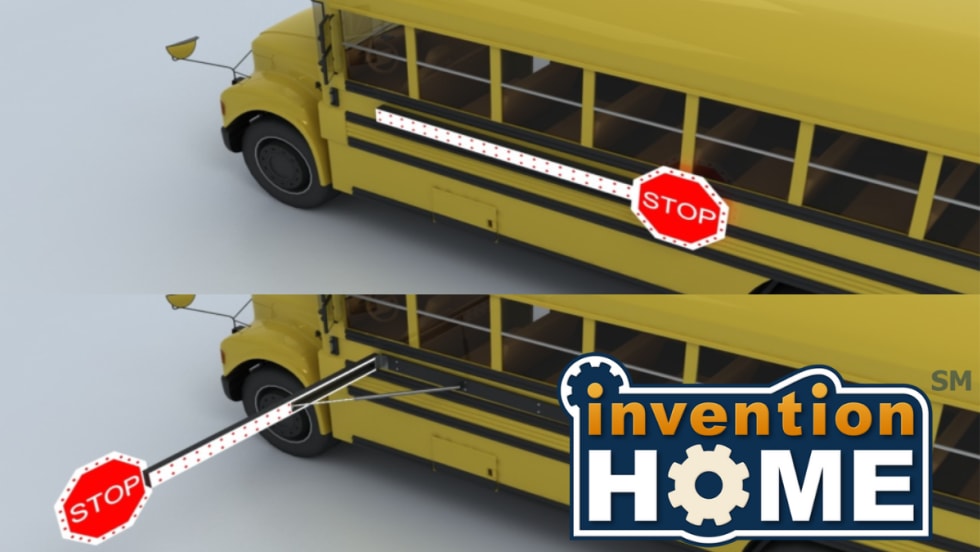

But putting that aside, here is a short list of improvements I have experienced: moving the starter from the floorboard to the dashboard; automatic transmissions; padded seats (bottoms and backs); sealed beam headlights, halogen lights and light-emitting diodes; clearance lights; power steering (and, therefore, smaller steering wheels), tinted windshields and windows; single-pane windshields; airbrakes; power-assisted brakes, antilock brake systems; air conditioning; tubeless tires; diesel engines; fuels (unleaded gasoline, green diesel, liquefied natural gas, ethanol, liquefied petroleum gas, etc.); compartmentalized seating; safety restraints for drivers and for occupants; wheelchair securement devices (attached to sidewalls until late in the 1980s when wheelchair placement changed to a forward orientation); roof-top ventilators/escape hatches; emergency windows; alarms (backing, emergency exit, post-trip inspection, etc.); “coolant/antifreeze” instead of just antifreeze; fire-retardant seat fabrics; synthetic seat padding; video surveillance equipment; computerized operational links and diagnosis terminals; maintenance-free batteries; lighted white-on-red octagonal stop arms (replacing flags and trapezoidal red-on-white stop signs); crossing control arms; under-body storage compartments (hopefully replacing exterior above-roof and interior top-mounted storage compartments); emergency reflective triangles replacing flares; fire extinguishers; body fluid cleanup kits; cell phones and other communication devices; GPSs. Wow! Let me stop and allow you to add to the list!

Ted Finlayson-Schueler has described innovations in training, but let me put in my “two cents worth.” In the mid-1970s, NHTSA developed (or caused to be developed) some good school bus driver training manuals, which helped to standardize training throughout the industry. As needs arose to incorporate additional topics, state departments of education and/or motor vehicles responded with modifications to their respective syllabuses. Besides pre-commercial driver’s licensing training and defensive driving techniques, among the many topics with added emphasis have been cultural diversity, sensitivity training, transporting preschoolers (including Head Start) and children with special needs (including wheelchair and other occupant securement procedures), dealing with behavior problems, terrorism, interpersonal relationships, communication and dealing with aggressive drivers and road rage.

For training presentations, blackboards were replaced by green boards and then by white boards and flip charts; 16-millimeter films were replaced by videotapes and DVDs; overhead projectors are being replaced with LCDs. (Isn’t PowerPoint a great presentation tool?!)

Bar must be raised

Our safety record is good, thanks to the evolution of equipment, training and improved performance. Unfortunately, some of the innovations in our industry are the result of human failure: various federal and state statutes, crossing-control devices, backup alarms and post-trip inspection alarms, for example.

Changing from a vastly agrarian to an industrialized to a technology-based society has increased the pace and the complexities of daily life. As long as driver distraction and inattention to the details of the daily task of safely transporting our nation’s future to and from school and school-related activities continue to be the major causes of student injuries and fatalities, the next 50 years must see a concerted effort to raise the level of performance of school bus drivers and attendants to all-time highs and to change behaviors of the motoring public at large. Raising expectations and levels of accountability are a must.

George Horne is a school transportation consultant and president of Horne Enterprises in Metairie, La. He can be reached at (504) 456-0141 or chestnut38@aol.com.

Computerized Routing and Scheduling

By Derek Graham

In 1982, I was a graduate student in the Operation Research Program at North Carolina State University. My summer job was to work with a professor looking at options for routing and scheduling school buses using computers. I spent many days with a large paper map measuring distances between stops using a map wheel. The technology we observed and tested was on mainframe computers and, while efficient solutions could be generated, updating and maintenance capabilities were very limited.

In 1981, IBM introduced the first personal computer (PC), which came equipped with 16K of RAM and one or two 160K, 5 1/4-inch floppy diskette drives.

By 1986, computer routing systems began movement from mainframe and mini-computers to PCs. Putting computer-assisted routing on the desktop of any transportation manager transformed the industry. It enabled school districts of any size to expand their capabilities by tapping into this powerful technology.

On pins and needles

Prior to computer-assisted routing systems, the key planning tool for many school districts was the “pin map.” This map was often mounted on a bulletin board so that various colors of push-pins could be placed at student locations and bus stops. String or yarn could then be wrapped around those pins to designate bus routes. I often wondered what would happen if someone brushed up against that map and a few hundred pins were knocked to the floor!

When North Carolina installed a computer-assisted routing system in each public school district during a five-year period beginning in 1986, the maps had to be digitized by hand. Student data had to be loaded one school at a time (five diskettes per school!), and maps were generated using a pen plotter. The plotter was fascinating to watch as it drew each road, bus stop and street name character individually.

Now, up-to-date maps are available from local government GIS departments, student data are accessed via networks and inkjet plotters produce beautiful output in minutes rather than hours.

<> Today’s tools save money

Today, local and wide area networks, high-powered PCs and the Internet provide access to routing information across the school district. Districts can use these tools to adjust rapidly to changes or emergencies, develop alternative plans and test them in simulation before putting them into place, savings thousands of dollars.

Maps, student locations and bus stop locations are being used not only to develop efficient routes, but to provide essential information for district planning. Expanded uses for these data include improved student safety using global positioning and automated vehicle location — even ridership monitoring using smart cards or RFID (radio frequency identification).

In 1982, we could scarcely conceive of an optimized routing system that could be updated daily, graphically, on desktop computers. Internet resources such Yahoo Maps (shortest-path driving directions) or Google Earth (satellite images) were unheard of.

Just as the technology has advanced amazingly in the past 20 years, it is exciting to think of the ways that graphic and geographic data will be used to support school transportation operations in the next 20 years!

Derek Graham is the section chief of transportation services for North Carolina’s Department of Public Instruction.