About 14% of public school students rely on compassionate and empathetic bus drivers who are properly trained to help special-needs students reach their academic goals and achievements.

They are among the most vulnerable children in the educational setting: children with special needs. Beset with often daunting difficulties, they are entitled to an education in this country, to reach for their individual goals and achievements, just like every other child. The weighty responsibility to safely transport these children to their places of learning falls on the school bus driver.

And their job keeps growing.

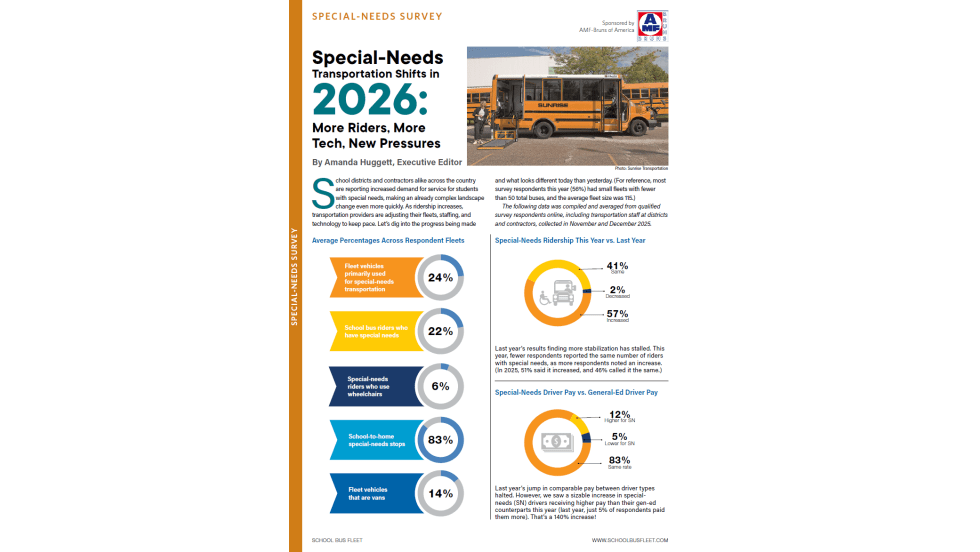

Today, according to the latest U.S. Department of Education figures, some 7.3 million children – 14% of all public school students – are served by The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), which mandates a free and appropriate public school education to children and youth ages 3–21 with disabilities. Those numbers jumped significantly from 4.7 million students in 1990 to more than 6 million in 2001 and have steadily increased in the last three decades.

The rising numbers can be attributed, in part, to health research advances and training that have provided better diagnoses and treatment for an ever-wider range of conditions. Once, school bus drivers of children with special needs may have dealt with wheelchairs and other readily apparent physical impairments, today they are expected to care for children with different needs related to cognitive concerns, behavioral issues, and an extensive span of medical conditions.

Drivers also may now transport very young children – toddlers and infants with special needs in the federal Head Start and Early Head Start programs. Instituted in 1965 to provide educational assistance to underserved preschool children, these programs now serve special-needs preschoolers and infants. Transportation of these littlest students requires special car seats and other accommodations.

Still another development affecting school bus drivers’ duties has been the “mainstreaming” of children with certain disabilities who are placed in regular classroom environments – and on school buses with their nonchallenged classmates. So, today’s school bus drivers who don’t routinely transport special-needs students also may require training in behavior management techniques for children with autism and emotional disturbances or psychological disorders.

“Some 95-100% of school buses in Pennsylvania transport a special needs student,” says Shae Harkleroad, owner of Raystown Transit Services, a bus transportation provider to three school districts in the state’s central region.

What Training Resources are Available?

Clearly, school bus drivers bear an extra layer of responsibility in safely transporting special-needs students between school and home. That extra burden merits suitable training and education.

State and local governments and school districts stipulate laws and/or guidelines covering the transport of special-needs students. These most often detail specific protocols but may not provide in-depth training. In many cases, a uniform training program is lacking.

“Pennsylvania has the best school bus transportation in the nation,” says Harkleroad, a 25-year industry veteran. However, he adds, no formal special-needs training exists at the state level, so each district or service provider must determine the level and content of special needs training, based on their needs.

The National Highway Transportation Safety Administration (NHTSA) presents an online six-session module on its website, www.nhtsa.gov. The module, “Transportation of Children with Special Needs,” covers types of disabilities and behaviors, team communications, specialized equipment, loading and unloading, and emergency situations.

Many school bus service providers post tips and guidelines for special needs drivers on their websites. Others, such as The School Bus Safety Company (SBSC) and First Student, offer comprehensive training programs.

SBSC recently issued a complete update of its 10-year-old training course, Transporting Students with Special Needs, to reflect changes in technology, training techniques, legislation, and terminology.

The eight-session, video-based course is built around a “Safety Management System” that identifies transportation hazards and “trains the safe behaviors to remove these hazards,” says Jeffrey Cassell, SBSC president and founder.

Reviewed “with a fine-tooth comb” by experts, he says, the new course features session exams and a sharper, more focused narration. “We owe it to drivers to give the best training to safely transport the children in their care,” explains Cassell.

How Can Drivers be Better Prepared?

It’s all about keeping children safe. Training programs can always improve to better teach drivers about the challenges presented by special-needs students, as well as strategies to help forestall difficult situations. Education/training can be standardized across regions or jurisdictions. Aides/monitors or trained staff can be assigned to each bus carrying special-needs students to assist while the driver concentrates on driving.

A critical improvement would be bus driver involvement in Individualized Education Program (IEP), a written document developed for each special-needs student, detailing their goals for the year, and determining specific support services required for the child.

“Without knowledge of the IEP, drivers are left guessing regarding a child’s behavior or extent of their disability. It’s difficult for drivers to make a connection without the input from an IEP,” Harkleroad says. “All the training is for naught if you don’t know a student’s background.”

In districts where his drivers are allowed to access IEPs of students on their routes, Harkleroad keeps the IEP documents under lock and key in his office to preserve confidentiality.

With the IEP as a focus, a team approach with district and school staff, parents, monitor/aide, and drivers is essential. “Teamwork. It needs all of the partners to work together,” says Cassell. “It’s also important for drivers to inform the team when a strategy doesn’t work on the bus.”

Good communication and sharing successful strategies will help ensure the journey to school and back home is safe and comfortable experience, agreed Cassell.

Special-Needs Drivers: Compassionate, Caring

The bus driver, along with the teacher, is most often the one constant in a child’s educational experience. For most special-needs school bus drivers, many of whom are retired seniors opting for a second career, the job is a labor of love.

“These are drivers who are care about people, who bring a compassion and empathy to their jobs,” says Harkleroad. “They develop relationships often lasting a child’s entire educational career and frequently refer to these students as ‘my kids.’”

Drivers are part of the solution in a special-needs child’s positive educational experience. “They have the same wants and needs as other children: positive reinforcement, a smile, courtesy,” Harkleroad explains.

He singled out one of his drivers, Angel Bartel, the mother of an adopted autistic child. She has transported special-needs children to school for the past six years.

“She is keenly aware of how important it is to put parents at ease by letting them know their children are in good hands with her,” Harkleroad says. “She also puts the students at ease with her cheerfulness and calmness when around them.”

Compassion and empathy are perhaps the most important qualifications for a special-needs school bus driver not found in a training course.