Are there social factors impacting safety in the area, such as drug houses or convicted sex offenders living nearby?

Finlayson-Schueler goes further to suggest that drivers evaluate stops on a daily basis. “Even a well planned bus stop can become unsafe if traffic patterns change, landscaping is planted or grows out of control, an unknown adult is loitering near the stop, new signs or buildings are erected, threats are made to the bus or driver, or there are changes in the number or age of children at the stop,” he explains. “Bus drivers are the eyes and ears of the transportation department, and no detail is so small that it should not be reported.”

Ellis also recommends that stops be situated to avoid dangerous crossovers. “There are still places where very young children are expected to cross 55 mph, multi-lane highways,” he says. “Maybe there are situations where they are unavoidable, but I don’t care how well you train a child or how much the penalty is for passing a stopped school bus, something’s going to happen there.”

Equipment boosts visibility

Through recent redesigns of bus hoods and development of Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards (FMVSS) for mirrors, manufacturers and the federal government have helped to improve visibility around the bus, Finlayson-Schueler says.

While blind spots around the bus have been reduced, accurate mirror adjustment is still vital for monitoring the danger zone. According to Fischer’s experience, most school bus drivers neglect to set the crossover mirrors to meet FMVSS 111, the regulation addressing mirror adjustment using the field-of-view test.

“The drivers are using them as driving mirrors to see to the rear, not to the front of the bus,” and this reduces the field of vision from 12 feet to 4 feet in front of the vehicle, Fischer says.

Finlayson-Schueler recommends that schools and bus companies paint a mirror grid on the bus yard pavement so that drivers can check their mirrors daily.

Ellis calls the field-of-vision test one of the most productive training sessions for bus drivers, and he says he is better able to help drivers learn, while avoiding singling anyone out, by turning the test into a game.

With a bus parked in the parking lot, Ellis blindfolds drivers, and then places items in the danger zone, like orange hazard cones. Next, he removes the blindfold and times the driver to see how long it takes for him or her to find all the items.

“It’s really very instructive, even for veteran drivers who have been driving for a long time,” Ellis says. “Sometimes it’s an eye-opener. Many drivers kind of give mirrors short shrift. They’ll glance at them, but unless the driver really searches those mirrors, really moving in the seat to change the angles of vision as they’re looking in those mirrors, they’ll miss a child.”

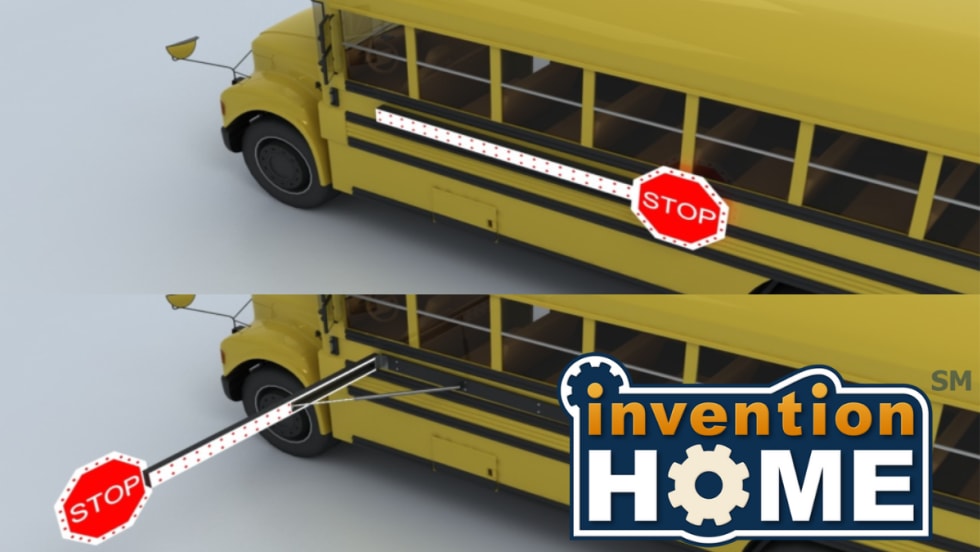

The crossing control arm that aims to force children to walk farther out in front of the bus when loading and unloading so that the driver can see them has been mandatory equipment for public school buses in North Carolina since the 1980s. Graham credits the devices with the decrease in the number of by-own-bus fatalities in the state. “We believe very strongly in the benefit of the crossing control arm, and our state has argued, at least for the last two National Congresses on School Transportation that I’ve been involved in, to make them a [nationwide] requirement, but that hasn’t come to pass yet,” he says.

Others, however, caution against relying too heavily on crossing arms. “I am not a big advocate of them because there have been by-own-bus fatalities with crossing arms,” Ellis says. “I think they sometimes give a false sense of security.”

Stop arm violations persist

Stop arms and flashing lights on school buses notify passing motorists that the bus is loading or unloading. Despite this, stop arm violations happen frequently and aren’t likely to be completely eliminated. Ellis compares the challenge to stopping motorists from running red lights.

Graham notes that in North Carolina, motorists pass stopped school buses 2,000 times a day. “You have to do continuing enforcement and education to get the word out to the public. But you also have to plan for the eventuality that you’re not going to get the word to everybody. So drivers and students have to go under the assumption that other vehicles just may not stop,” he says.

Ellis points out that there have been cases of vehicles passing a stopped bus on the passenger discharge side. He says children must also be trained to pause at the bottom step of the bus before exiting and to look to the back of the bus to make sure no vehicles are attempting to pass on the right.

“Districts and drivers that really take this seriously even have older kids stopping at the bottom step,” Ellis says. “Kids will rise to the occasion of what drivers expect of them.”

How parents can help

Experts stress the important role parents play in reinforcing safe school bus procedures. Ted Finlayson-Schueler of Safety Rules! notes that the 2005 National School Transportation Specifications and Procedures suggests that parents and guardians should assist their children in understanding school bus safety procedures. The specifications also state that parents or guardians are responsible for the conduct and safety of their children at all times prior to the arrival and after the departure of the bus at a stop.

“If a child has to cross the road to the bus in the morning, the parent should wait for the bus and follow the safe crossing signal and procedure, just as the child would be required to do if the parent was not present,” Finlayson-Schueler says. “This modeling of safe bus stop behavior will be a powerful safety lesson for their child.”