Those of us in the pupil transportation community who have been working to perfect the process of loading and unloading students at school bus stops for the past 40 years or so have been wildly successful, but is there more room for improving safety?

The national school bus loading and unloading fatality survey — now compiled by the Kansas State Department of Education’s School Bus Safety Unit — identified as many as 75 students killed in the loading zone in one year in the early 1970s. Today, the annual number hovers around 10, even though the total number of students transported has more than doubled.

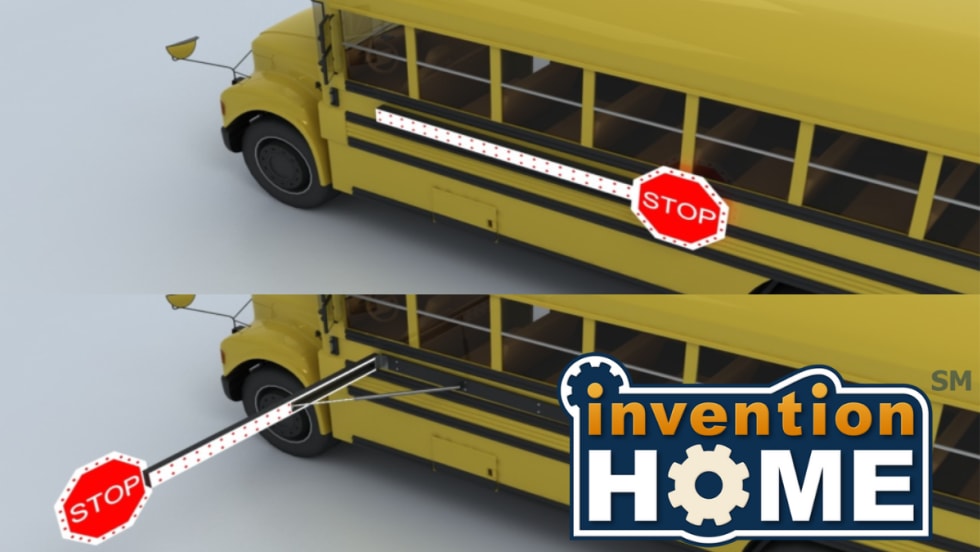

This accomplishment has been a joint effort of school bus driver and student training and equipment improvements. (Efforts to change the behavior of other motorists have not been so successful.) School buses are equipped with stop arms, crossing gates, improved mirror systems, eight-light warning systems, and radically redesigned hoods that create exceptional visibility.

The federal CDL supplement, the National Congress on School Transportation, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration’s driver in-service, the National Safety Council, and the training programs of major contractors as well as many states — the latest being North Carolina — are integrating driver signals to children as a part of the safe crossing process.

If zero fatalities and injuries is the ultimate goal, then this success leads us to ask, “What’s next?” The expert witness work that I do gives me an insight into what is going wrong out there in the yellow bus world.

Common cases

One recent trend that I have observed is missed bus stops, which are planned stops that don’t happen for one reason or another.

Often the child misses the bus because he or she is late to the stop or the driver is early. Sometimes the driver just misses the stop — maybe it was the first day for that pickup, or the child often isn’t there. Whatever the reason, the stop doesn’t happen the way it was planned.

What happens next is anybody’s guess, because we haven’t given our drivers and students any training about what to do. The only counsel I have seen is direction to the driver to not back up at the stop, but to instead go around the block.

Backing has obvious dangers, but it has not been a part of any of the scenarios I have become familiar with. Going around the block can be a simple solution in some areas, but it can be very complicated in many situations.

In the cases for which I was an expert witness, students were struck by another motorist. The three variations that lead to such a crash are:

• A student was running late and crossed the street to get to a neighborhood stop or to a stop farther along the route, and the school bus was not even in sight.

• The school bus was returning to the stop, and neither the student nor the driver had a plan for how they would negotiate that pickup.

• Students were going to a “makeup” bus stop that the school bus driver created because he or she was sorry for the kids missing the bus.

Here’s a closer look at those three types of scenarios and the risks they present.

1. The student rushing to the next stop

For the student rushing to another school bus stop who is struck crossing a road, there needs to be a plan for her to get to school if she misses the bus, because it is her fear of missing the bus that is making her abandon her normal pedestrian skills.

Of course, this means the school also has to have a plan. Is there a number that can be called to have a bus swing back by and pick up the student? Has that number been disseminated to parents and students?

What are your policies and procedures for this situation? Is there a “What to do if your child misses the bus” section in your transportation information that is shared with parents at the beginning of the school year?

I’m not suggesting that you open a taxi service. If children miss the bus regularly, then conversations need to take place and consequences need to be enforced. But the bottom line is that if there isn’t a plan that has been disseminated to students, parents, and drivers, then your school bus driver might make up his or her own plan, which is seldom a good idea.

There needs to be a plan for the student to get to school if she misses the bus, because it is her fear of missing the bus that is making her abandon her normal pedestrian skills.